Well, I gave it a shot.

I heard about a Thursday-night comedy open mic at a bar on Dolores Street not far from my house. I walked down earlier this evening to check it out.

I arrived just as the show was about to begin, There were only a few folks sitting at the bar, plus a few others shooting pool in a nook toward the rear. Everyone had their backs to the small stage and microphone stand.

By the front door, a half dozen nervous comics were sitting around as if waiting for the results of a blood test.

Brady, the evening’s MC, took the mic off the stand and said hello to everyone. No one turned to look at him, just the nervous comics.

When the first guy got up, despite no one paying attention, he launched into his set, but it was hard to hear. I tried to keep my focus on him, and I laughed when he presented each premise, but I couldn’t quite catch his punch lines. The next comic was equally hard to hear.

Finally, this one comic got up, one with questionable pronouns. They did great! I could hear them perfectly. Clearly, they’d had some prior public-speaking training. Though they were reading off notes on their phone — something I’ve been told to avoid — I really did enjoy their energy.

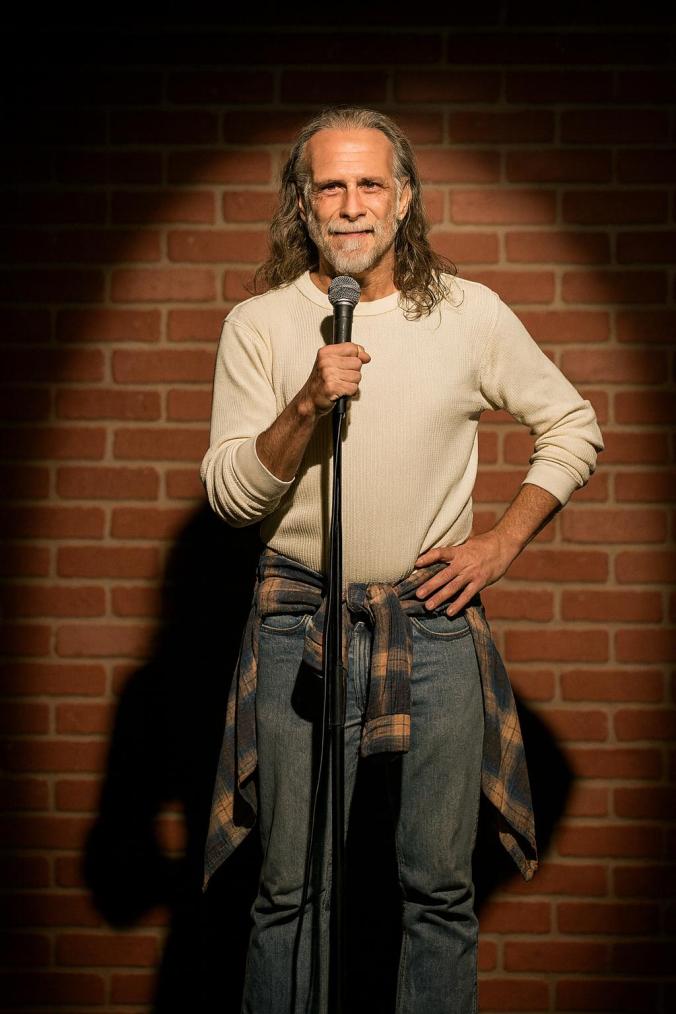

Then the MC called my name.

All day, I’d been rehearsing this bit I’d written about the Ohlone Indians. Soon as I got up to the mic, I knew that no one would listen. So I decided to simply practice reciting my memorized lines at the microphone. I did get one laugh from one of the other comics. Mosly, I got nothing. Two-and-half minutes passed like two-and-a-half hours.

All in all, I’d say it was a bomb — the whole show! But bombing can be a blessing.

Everyone busts their cherry some time, and now I’ve busted mine. It was good to get a chance to practice speaking while holding the mic. Good to get a chance to keep addressing different parts of the room. Good to lose my place at one point and then recover from an awkward pause. No one was listening, so none of it mattered.

After the last comic performed, the MC thanked the patrons in the bar — none of whom seemed remotely aware that comics had been performing.

How surreal!

Still, afterward, I got to know a few of the comics, most of whom were heading out to another open mic at another club. They invited me along, but I was wrecked after busting my cherry, so I walked back home while they caught the bus up to Market Street.

Even though the event was a bomb, I’m grateful to have gotten a chance to practice — and to meet some other comics and exchange our contact info. I look forward to seeing them again and joining them on the open-mic circuit all over San Francisco.

How About You?

When was the last time you tried something new, only to discover it may be more challenging that you thought? Let me know in the comments.