While out on one of my afternoon walks here in San Francisco, I found a sidewalk library full of free books for the taking — no library card required.

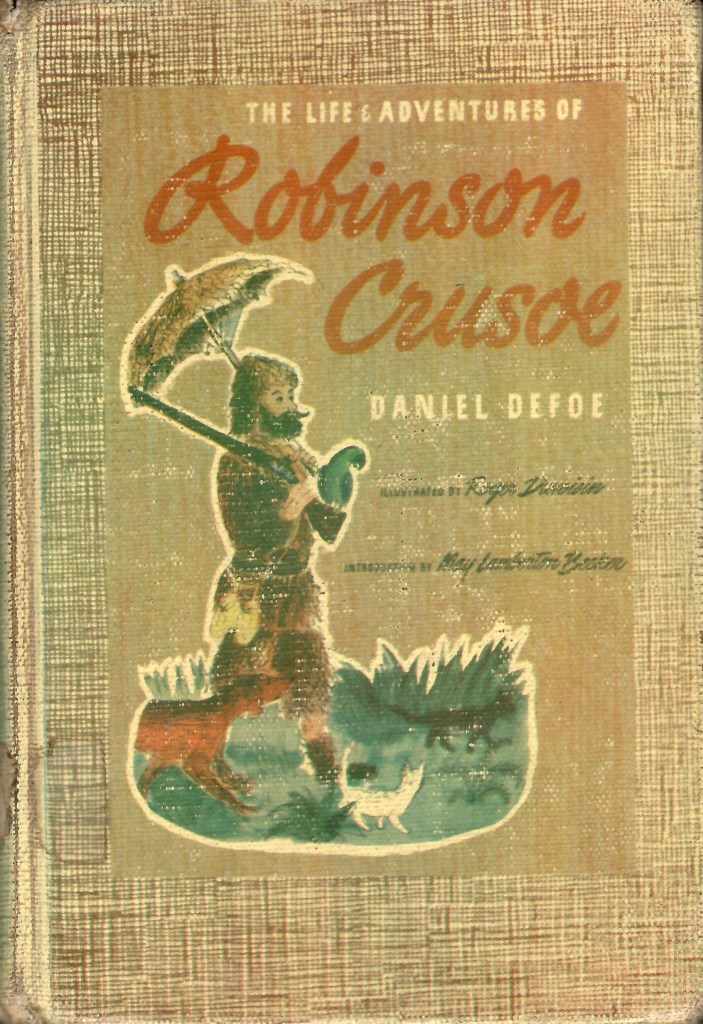

Among the many volumes jammed across the two small shelves was an old, ragged, cracked-spine, yellow-paged, 1946 edition of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

Despite my senior age and three degrees in English, I had never read Defoe’s classic tale of shipwrecked adventure. So, opening the sidewalk library’s plexiglass door, I plucked the antique volume off its shelf, tucked it under my arm, and headed home to read.

Surprise! Surprise!

Three paragraphs into chapter one, I was pleased to discover several references to ancient Taoist ideas.

Of course, it’s highly unlikely that Daniel Defoe was aware of Lao-Tzu and his Taoist Book of the Way. Afterall, earliest translations into English of the Tao te Ching did not first appear until the late 19th century — more than 150 years after Robinson Crusoe was originally published in 1719.

Still, Taoist ideas lay the foundation of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

What is the Tao?

In ancient Chinese philosophy, the Tao, or the Way, represents the organic energy of life, the effortless flow of the universe. It’s the power of a river as a mountain’s melting snowfall rages toward the summer sea; conversely, it’s also the icy crust of a frozen pond in winter. Neither good nor bad, neither up nor down, neither in nor out, the Tao is comprised of all these and — mostly — everything in between.

One of the main concepts of Taoism is the idea of wu wei. Wei means any contrived action, any attempt made to thwart the natural flow of nature. Wu means no, so wu wei suggests the idea of no contrived action, of no action that goes against the flow of the Tao. Wu wei is often described as nothing, meaning no thing — that is, no thing other than the natural Tao.

Taoist Reflections

Early in chapter one, Robinson Crusoe’s father’s attempts to dissuade his son from running off to become a sailor. The father encourages his son to accept his natural status in life as a modestly well-to-do citizen, enjoying the pleasures provided by the “upper station of low life.” Such a life, the father assures his son, is the envy of both paupers and kings.

This “middle state” of society suggests the middle Way encouraged by the Tao, where extremes are best avoided, where “the high is lowered” and “the low is raised.” As stated in the Tao te Ching, what’s “most complete seems lacking,” and yet “those who are content suffer no disgrace.” Indeed, those who know when to stop chasing the wild dreams of youth go “unharmed” and “last long.”

The Tao of Retirement

Robinson Crusoe, only 18 when his story unfolds, ignores his father’s wise advice. Rather than accept the natural course of his upper-middle-class existence, he follows his dream of a life on the ocean. Soon enough, having defied both his father and the Tao, young Crusoe will eventually endure his inevitable, isolated fate.

With this early moment in the book, Defoe reminds me that there is no shame in living a simple retirement, of sitting on a porch at dusk, watching the daylight fade away into the cool embrace of night. I wish I could be satisfied with such a simple retirement. Perhaps such a fate will await me as I snuggle up to eighty. For now, though, in my mid-60s, I dream all sorts of sea-faring dreams.

Hopefully, such dreaming will not lead me to repeat Robinson Crusoe’s sad and seemingly lonely fate.

How About You?

What are your thoughts and plans for retirement? Let me know in the comments.